These projects are explorations of what it means to delve into my cultural identity and heritage as I’ve grown older as an Asian-American child of refugees with themes of war, generational trauma and resiliency, and the visual language of complex family/personal dynamics.

Bloodletting

In the summer of 2025, Elinor Kry traveled to Vinh Long, Vietnam in an attempt to understand why her mother had recently left the US and moved back to the country she was forced to leave 44 years ago as a child refugee, seeking lineage and a sense of home.

Upon arriving, Kry was struck by how unfamiliar and distant her mother had become. She had become bony like the chickens she raised, darker skinned from laboring in the fields, her demeanor sharper yet newly confident. The only thing that seemed unchanged was her mother’s flourishing love for growing plants like dragonfruit, ginger, and countless others.

Over time, it became clear that her mother’s return was marked not by belonging but by violent and disorienting attempts to reintegrate into Vietnamese life. The roots and connection with her family she had hoped for remained out of reach. Her relatives bore the same scars of war, and their demonstrations of affection masked a transactional dynamic based on her mother’s position as a Vietnamese-American.

Witnessing these tensions reshaped Kry’s perspective of the distance that had grown between her and her mother. Her mother was tending to not just plants, but the abandoned child that had defined her for decades. Kry holds onto the version of her mother that she once knew, and learns to see the version she was becoming.

In the summer of 2025, Elinor Kry traveled to Vinh Long, Vietnam in an attempt to understand why her mother had recently left the US and moved back to the country she was forced to leave 44 years ago as a child refugee, seeking lineage and a sense of home.

Upon arriving, Kry was struck by how unfamiliar and distant her mother had become. She had become bony like the chickens she raised, darker skinned from laboring in the fields, her demeanor sharper yet newly confident. The only thing that seemed unchanged was her mother’s flourishing love for growing plants like dragonfruit, ginger, and countless others.

Over time, it became clear that her mother’s return was marked not by belonging but by violent and disorienting attempts to reintegrate into Vietnamese life. The roots and connection with her family she had hoped for remained out of reach. Her relatives bore the same scars of war, and their demonstrations of affection masked a transactional dynamic based on her mother’s position as a Vietnamese-American.

Witnessing these tensions reshaped Kry’s perspective of the distance that had grown between her and her mother. Her mother was tending to not just plants, but the abandoned child that had defined her for decades. Kry holds onto the version of her mother that she once knew, and learns to see the version she was becoming.

Yearning for Closeness

‘There is a sense of loneliness that can mark the immigrant experience, that makes immigrants always searching for home...the act of immigration is bound up with memory.. all water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.’ Toni Morrison

Photographed in the summer of 2023, It was my mother’s first time back in 25 years and meeting all of her extended family since she was a child. Since this trip, she has now moved back to the rural province of Canh Long after living in America for over 40 years. A continuing photo series, I yearn to grasp and understand this jarring transition she has taken on, building a house and starting her life over. At the time, her return raised a question: Do immigrants ever truly assimilate? And if they choose to return, does the land welcome them back?

‘There is a sense of loneliness that can mark the immigrant experience, that makes immigrants always searching for home...the act of immigration is bound up with memory.. all water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.’ Toni Morrison

Photographed in the summer of 2023, It was my mother’s first time back in 25 years and meeting all of her extended family since she was a child. Since this trip, she has now moved back to the rural province of Canh Long after living in America for over 40 years. A continuing photo series, I yearn to grasp and understand this jarring transition she has taken on, building a house and starting her life over. At the time, her return raised a question: Do immigrants ever truly assimilate? And if they choose to return, does the land welcome them back?

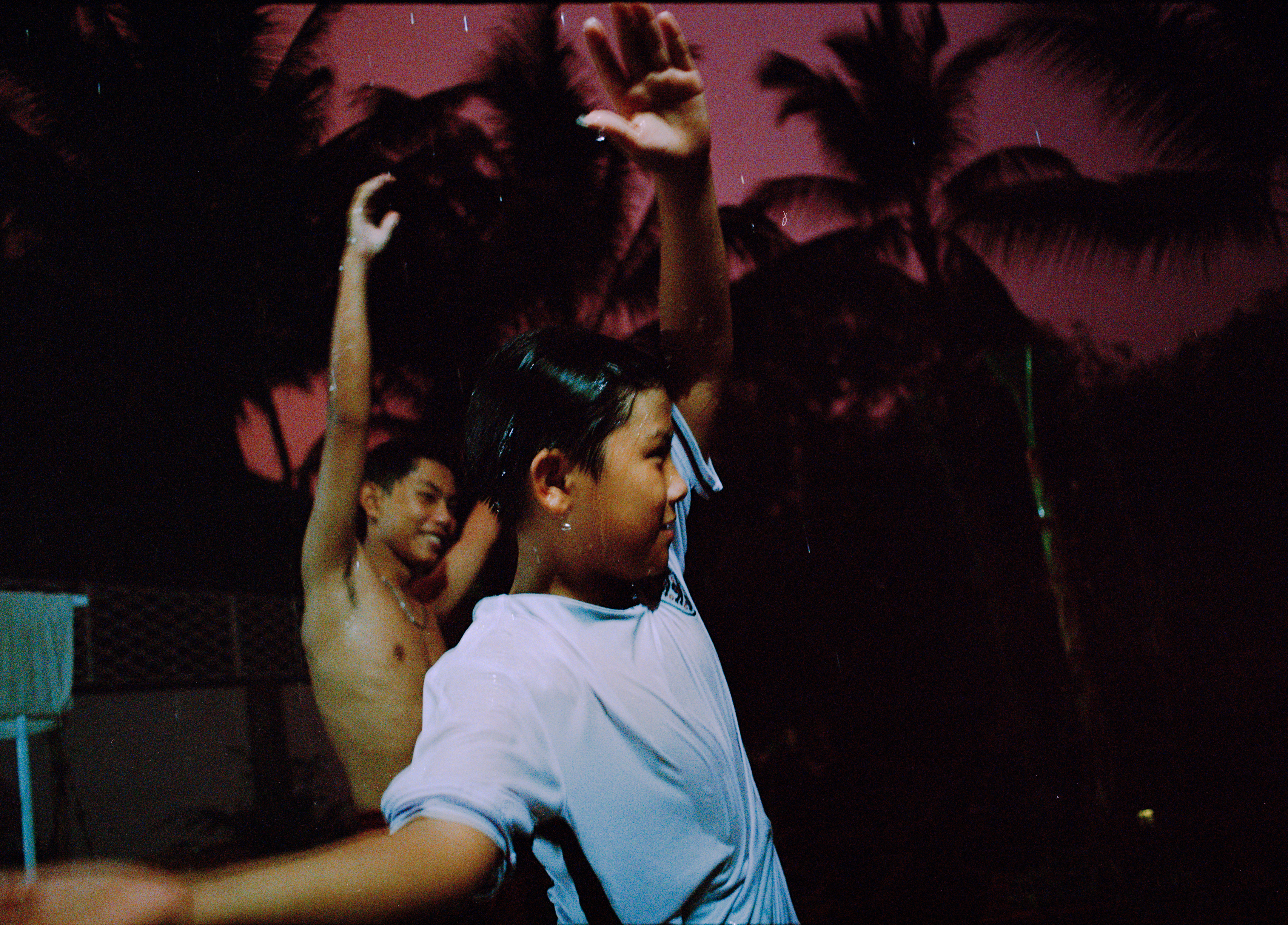

In Cambodia, I live to see the change

My father was 5 years old when his mother carried him across land mines alongside his siblings to escape the Khmer Rouge and the Cambodian Genocide in the 1980s, where they were sponsored by a church to immigrate to the US. Growing up, this traumatic history was never spoken about and I was isolated from my relatives due to living far away. When I moved to the east coast when I started college, I used the camera to try to develop a relationship with my family in Danbury, Connecticut. This inspired a trip back to Cambodia where I spent a few days with family in S’ang, Cambodia. My first experience of Khmer culture, and the negativity that I long associated with Cambodia was replaced with the content, energy, and hope that I discovered within my familiy there - innoceont of tragedies past or present insecurities.

My father was 5 years old when his mother carried him across land mines alongside his siblings to escape the Khmer Rouge and the Cambodian Genocide in the 1980s, where they were sponsored by a church to immigrate to the US. Growing up, this traumatic history was never spoken about and I was isolated from my relatives due to living far away. When I moved to the east coast when I started college, I used the camera to try to develop a relationship with my family in Danbury, Connecticut. This inspired a trip back to Cambodia where I spent a few days with family in S’ang, Cambodia. My first experience of Khmer culture, and the negativity that I long associated with Cambodia was replaced with the content, energy, and hope that I discovered within my familiy there - innoceont of tragedies past or present insecurities.

Grandma Ted

a series documenting my foster Grandma, whom was my mom’s spanish teacher and adopted her in high school. we were very close when I was a child but grew distance. these photos helped me attempt to understand the distinct societal and cultural differences between us and my mother that have become apparent as i’ve become an adult.

a series documenting my foster Grandma, whom was my mom’s spanish teacher and adopted her in high school. we were very close when I was a child but grew distance. these photos helped me attempt to understand the distinct societal and cultural differences between us and my mother that have become apparent as i’ve become an adult.